Kentucky’s Drug Crisis: Battling Opioids, Meth and Fentanyl in the Bluegrass Kentucky’s battle with drug addiction

- Aug 2, 2025

- 28 min read

Updated: Aug 24, 2025

The Scope of an Epidemic

Kentucky’s battle with drug addiction is staggering in scale. In 2021, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the state’s overdose death rate soared to one of the highest in the nation – about 55.6 overdose deaths per 100,000 people, more than double its rate a decade earlier. Total fatalities peaked around 2,250 Kentuckians lost to overdose in 2021, marking one of the darkest periods of the epidemic. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 times stronger than heroin, was involved in the vast majority of these deaths. By 2023, 1,984 Kentuckians died from overdoses, roughly 79% of those deaths involving fentanyl. Another 55% of the 2023 fatalities involved methamphetamine, reflecting a surge in stimulant abuse alongside opioids.

Though the death toll remains devastating, recent data offers a glimmer of hope. Kentucky recorded a decline in overdose fatalities for three consecutive years – the first sustained downturn since the crisis began. In 2024, overdose deaths fell dramatically to 1,410 statewide, a 30.2% drop from the year prior. This follows smaller declines of 9.8% in 2023 and 2.5% in 2022. Officials credit the progress to an all-hands effort in prevention, treatment and enforcement. “I am thankful that more Kentuckians are alive and in recovery today compared with last year,” Governor Andy Beshear said in May 2025, while cautioning that “we still mourn and grieve” the 1,410 lives lost in 2024 and all those before. Every life lost, he noted, represents “someone’s mom, dad, son, daughter and loved one” – and the mission won’t stop “until every Kentuckian is saved from addiction”.

Behind the overdose numbers are even larger ranks of those struggling with addiction. A recent study estimated that about 5.9% of Kentucky adults suffered from opioid use disorder in 2019, with some counties in Appalachia seeing opioid addiction rates as high as 17% of the adult population. Such prevalence is almost unheard of, underscoring how deeply entrenched opioid abuse has become in certain communities. And opioids are only part of the picture – thousands more Kentuckians battle meth or other substance addictions, often in dangerous combination. Kentucky’s Office of Drug Control Policy notes that fentanyl and meth now “continue to be the most prevalent drugs contributing to overdose deaths in the state”, co-appearing in a great many fatal overdoses.

The fallout extends beyond the health sphere into public safety and social stability. Law enforcement officials describe a ripple effect of increased crime tied to the drug trade and desperate users. “Heroin, fentanyl and other dangerous drugs are increasingly available in Kentucky communities with deadly consequences,” warns the U.S. Attorney’s Heroin Education Action Team (HEAT) in the Eastern District of Kentucky. The rising tide of opiate abuse fuels violent and property crime, strains social services, and “is devastating Kentucky families”, robbing communities of thousands of citizens to addiction or overdose. In many Kentucky towns, jails and foster care systems have filled with the byproducts of the drug scourge – from low-level theft and burglary by those seeking drug money, to children orphaned or removed from homes due to parental substance abuse. As of 2023, Kentucky had one of the nation’s highest rates of kids in foster care, a crisis significantly exacerbated by parental opioid addiction and overdose deaths. The human toll has been multigenerational.

Yet amid this bleak landscape, Kentucky has started to bend the trajectory. Alongside the drop in overdose deaths, the state’s latest crime data also show promising trends. The rate of drug-related offenses fell by about 11.5% in 2024, part of an overall 8% decrease in serious crime statewide. Officials believe that robust drug enforcement combined with expanded treatment is making communities safer. “Every Kentuckian should be safe and feel safe, and no Kentucky family should feel the pain of losing a loved one to addiction,” Governor Beshear said, praising recent multi-agency crackdowns on drug trafficking networks. Still, for all the statistical improvements, the crisis remains a public health emergency of immense proportions. More than 1,400 lives lost in a year – roughly four Kentuckians dying from overdoses every single day – is a stark reminder that the fight is far from over.

From Pills to Fentanyl: How the Crisis Evolved

Kentucky’s drug epidemic did not erupt overnight; it has built over two decades through multiple waves. It began in the late 1990s and early 2000s with a flood of prescription opioid painkillers that were heavily marketed as safe solutions for pain. Appalachia, particularly Eastern Kentucky’s coal country, was ground zero for the OxyContin boom. Doctors, some at “pill mill” clinics, liberally prescribed high-dose opioids for chronic pain from mining injuries and other ailments. Pharmaceuticals like oxycodone and hydrocodone became ubiquitous in communities like Clay County, where virtually “everyone we met had a story about drug use – their own, a parent’s, a partner’s, a child’s”, recalls one researcher who spent months interviewing residents. The volume of pills flowing was staggering, and addictions took hold across generations.

Kentucky was an early adopter of reforms – creating a prescription drug monitoring program (KASPER) and shutting down pill mills – but as access to pain pills tightened, many dependent people turned to heroin. By the 2010s, a second wave of the crisis saw heroin flooding into Kentucky, especially in urban centers and northern counties near the Ohio border. Heroin, often cheaper and easier to obtain than diverted pills, led to a new spike in overdoses and crime. Treatment providers observed a stark shift: “Our facility saw a decrease in prescription opioid abusers and an increase in heroin patients from 2009 to 2014,” one Kentucky clinician noted, reflecting trends across the state. Law enforcement too had to pivot, targeting a growing heroin trade that brought violence and turf disputes.

Then came fentanyl, the game-changer. Beginning around 2015–2016, illicitly manufactured fentanyl – a synthetic opioid 50-100 times more potent than morphine – began appearing in Kentucky’s drug supply. At first it was mixed into heroin, but soon it infiltrated pills, cocaine, and other street drugs, often without users’ knowledge. By 2016, synthetic opioids like fentanyl surpassed heroin and prescription drugs as the leading cause of opioid overdose deaths in the U.S., a pattern mirrored in Kentucky. Local data show that “once mostly caused by prescription opioids … and later heroin, drug overdose deaths in Kentucky are now driven by the synthetic opioid fentanyl”. From 2019 to 2020 alone, Kentucky overdose deaths involving fentanyl nearly doubled, according to researchers. Fentanyl’s stealth and extreme potency have made every drug encounter a game of Russian roulette – as Wyatt Williamson’s story painfully illustrates, one counterfeit pill or a single hit can be lethal.

Complicating the crisis further is the resurgence of methamphetamine. Kentucky endured a meth lab epidemic in the early 2000s, which subsided after pseudoephedrine sales were restricted. But in the past decade, cheap, high-purity meth produced by Mexican cartels has poured into the state. Meth use exploded even as opioid deaths climbed. Increasingly, people mix stimulants and opioids – a dangerous practice known as “speedballing” or “goofballs” when combining meth with fentanyl. State overdose surveillance confirms fentanyl is now frequently found in combination with methamphetamine or cocaine in toxicology reports. This poly-drug pattern is deadly: stimulants like meth can mask opioid overdose symptoms or drive users to take higher doses, resulting in more lethal outcomes. “Data is starting to show increasing co-involvement with methamphetamine,” says Dr. Dana Quesinberry of the Kentucky Injury Prevention & Research Center, adding that these new trends demand further investigation.

The crisis has also continued to evolve through the COVID-19 pandemic. Isolation, economic stress, and disrupted services in 2020 led to a sharp spike in overdoses; Kentucky’s overdose deaths jumped 49% from 2019 to 2020, one of the highest increases in the nation. The pandemic years entrenched fentanyl’s grip. And now, yet another threat looms: xylazine, an animal tranquilizer often mixed with fentanyl, has been detected in Kentucky’s drug supply. While still emerging, wastewater analyses indicate broad geographic exposure to xylazine in Kentucky by 2023. Xylazine can cause flesh wounds and does not respond to naloxone, making the overdose reversal more complicated. Officials are monitoring this “tranq” dope hazard as the next frontier in an ever-changing drug landscape.

Through these waves, one thing has remained constant: the immense human cost. Each new phase of the epidemic has swept more Kentuckians into addiction – many starting with a doctor’s prescription, then shifting to street drugs as addiction tightened its hold. “I could walk into any doctor and say, ‘I’m a coal miner, my back hurts,’ and they’d say: ‘You need these [painkillers].’ Thirty Lortabs a day and a pint of vodka to sleep,” recalls Christian Countzler, a Kentucky resident whose opioid addiction journey spanned from OxyContin to heroin to meth and fentanyl. When the pills dried up, “that’s when heroin and fentanyl and methamphetamines surged. I started shooting dope… and that’s when things got really out of control”, he says, describing how he lost his job, family and home and ended up literally eating out of dumpsters. Countzler eventually found recovery and now helps others (his story continues later), but countless others have not been so fortunate. Understanding how the crisis evolved – from prescription opioids to illicit fentanyl and poly-drug use – is key to crafting an effective response.

Ground Zero: Eastern Kentucky’s Struggle

No part of Kentucky has been spared the drug scourge, but Eastern Kentucky – the Appalachian mountain region – has endured a uniquely severe burden. In economically distressed counties tucked in the hills, the epidemic struck early and hard. Places like Clay County, in the heart of Appalachia, were awash in “pill mills, meth labs, addictions and overdoses” by the 2000s, to the point that almost every family had firsthand experience with drug abuse. “Substance use disorder is the biggest public health challenge we are facing now here in Eastern Kentucky,” says Scott Lockard, Public Health Director for a multi-county district in the region. Data bear that out: the highest opioid use disorder rates in the state are concentrated in Appalachian counties, and the highest overdose death rates per capita are consistently recorded in mountain communities like Estill, Lee, Breathitt, and Floyd counties. Lee County, for example, recently reported the single worst overdose fatality rate in Kentucky despite the statewide decline in deaths. “It doesn’t matter who you are or what background you come from; everyone is susceptible to it,” notes Lee County Deputy Coroner Kenneth Lewis, who sees meth and fentanyl dominating local overdose toxicology reports and affecting residents young and old.

What made Appalachia so vulnerable? Economic hardship and social disintegration form the backdrop. Many Eastern Kentucky counties have lost coal mining and manufacturing jobs over the past decades, leading to deep poverty (over 30% in some counties) and low labor participation. In Clay County, for instance, nearly 39% live in poverty and fewer than 38% of adults are in the workforce. Such despair creates fertile ground for substance abuse. “There’s just nothing to do but drugs,” is a refrain locals shared time and again with researchers. Travis, a recovering meth addict from Clay County, explained how boredom and lack of opportunities paved his path to using: “There wasn’t nothing to do… That’s why I think everybody turns to drugs around here”. With recreation centers closed, theaters shuttered, and public parks disappearing, young people have few healthy outlets. The collapse of “social infrastructure” – the gathering places that knit communities together – has frayed the social fabric, isolating individuals and eroding hope. In such a void, drugs became a form of self-medication and escape, even as they fueled further chaos.

Pain and injury from manual labor have also played a role. Appalachian Kentucky saw aggressive marketing of prescription opioids in the 1990s targeting miners and loggers with chronic pain. As Christian Countzler noted, simply saying “I’m a coal miner” to a doctor all but guaranteed an opioid prescription. Generations of workers became hooked through legitimate medical channels. When enforcement finally cracked down on over-prescribing, many turned to illicit opioids readily available in the region via trafficking routes through Appalachia. Law enforcement in Eastern Kentucky has battled not only local dealers but also an influx of out-of-state drug networks exploiting the high demand. “We try to find out where the drugs come from, who is bringing them in,” says Joe Lucas, the sheriff of Lee County. His deputies coordinate with authorities down the line to trace suppliers, knowing that their rural county is an end destination for traffickers from bigger cities. But even as police make busts, new suppliers spring up, drawn by the profits to be made off vulnerable communities.

The human toll in Appalachia is etched in every corner. Jails cycle through people with substance-related offenses. Grandparents raise grandchildren because so many parents are incarcerated or deceased due to drugs. Kentucky’s Department of Public Health found that in 2022 alone, eight children in the state died from accidental drug ingestions and dozens more suffered nonfatal overdoses – heart-wrenching statistics that include toddlers who swallowed opioids in homes struggling with addiction. Hospitals in the mountains have seen a surge of babies born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) – infants trembling and crying from withdrawal because their mothers used drugs during pregnancy. Over three-quarters of NAS cases in Kentucky involve opioid exposure, often alongside methamphetamine. These babies face a fragile start to life, and their arrival often signals that another young family is in crisis.

And yet, for all its challenges, Eastern Kentucky is also demonstrating resilience. Community-driven efforts and a fierce determination to save lives are making a difference (as we’ll explore later in this article). In fact, a recent study noted that 14 of the top 20 U.S. counties with the greatest reductions in overdose mortality were in Eastern Kentucky. The Appalachian region, once seen only as the epicenter of the problem, is now becoming a testing ground for solutions. “We have tracked declining overdose mortality rates in Eastern Kentucky for several years now,” says Michael Meit, a researcher at East Tennessee State University. “What we have observed is an all-hands-on-deck approach, where policymakers, community stakeholders, and provider organizations have come together to expand access to treatment and build recovery supports. Our latest study provides further evidence of the good work happening in Kentucky.”. In short, Eastern Kentuckians are fighting back – and starting to win small victories against an overwhelming foe.

Families and Communities Shattered: Personal Stories

Behind every statistic in this crisis is a personal story – often a story of pain, loss, or redemption. In Kentucky, these stories span urban and rural, young and old, well-off and poor. Addiction has seeped into every kind of household. “It doesn’t matter who you are or what background you come from; everyone is susceptible to it,” as Deputy Coroner Kenneth Lewis reminds us. The stigma once attached to drug abuse has been replaced by a grim ubiquity: nearly everyone knows someone who has struggled.

Take the story of the Holman family in Lexington: In 2017, they lost their son Garrett to a fentanyl overdose – a single pill ordered online turned out to be fatal. Garrett’s father, Rob, has since channeled his grief into advocacy, testifying before Congress about the need to curb fentanyl trafficking. In Louisville, Julie Hofmans keeps her son Wyatt’s memory alive by crusading to educate others. Since his death in 2020, she has spoken at high schools across Kentucky, at drug prevention summits, and even helped push for a new Kentucky license plate that raises awareness about fentanyl. “If I can save another family from going through what I’m going through… I’m not going to stop at anything,” Hofmans says. For her, turning pain into purpose has been a way to cope – “I know I can’t save Wyatt, but I can try to save someone else’s child,” she explains. Countless mothers and fathers across Kentucky share similar missions, founding support groups, lobbying for stronger drug laws, or simply telling their stories to break the silence and shame that often surround overdose deaths.

In small towns, the impact is often intensely close-knit. When an overdose happens, entire communities feel the ripple. Consider Owsley County (population ~4,500), which in some recent years has had one of the highest per-capita overdose death rates. Each funeral is a community mourning. Volunteer fire departments and EMTs, who often know the victims personally, repeatedly revive the same individuals with Narcan or comfort the same families after tragedy strikes again. Stigma and shame have gradually given way to empathy and urgency. “We recognize that even while we celebrate progress, there’s a lot of heartbreak and pain because of this epidemic that continues,” Gov. Beshear said in 2024. The governor frequently meets with families who’ve lost loved ones, an acknowledgment that behind declining numbers are parents still setting an empty place at the dinner table.

For some, the journey goes from rock bottom to recovery – and those stories offer hope. One such example is John Bowman, a 42-year-old Kentuckian who spent half his life in and out of addiction’s grasp. By his own account, he “spent 24 years brawling with the beast of drug addiction,” cycling through jails and rehabs. In early 2023, John was facing a potential three-year prison term for drug-related charges. But a twist of fate and an innovative program gave him a second chance. He had entered Stable Recovery, a unique rehab initiative on a thoroughbred horse farm near Nicholasville. There, amidst rolling bluegrass pastures and prize-winning racehorses, John found an unexpected path to sobriety. He spent months caring for elite horses, learning to muck stalls, groom, and show up at dawn for barn chores – and something in him changed. “This program has taught me accountability, structure, discipline and responsibility,” John told a judge when pleading for leniency. Working with 1,000-pound animals gave him new confidence: “I look at it like this: If you can take care of a 1,300-pound horse, that paves the way for you to be able to take care of yourself,” John says. “I really don’t know why, but it does”. The judge was so moved by John’s transformation that he opted to send him back to the farm program instead of prison. Today, John Bowman is sober, employed as a program director at Stable Recovery, and reunited with family. “I think this is probably the most proud [my mother] has ever been of me,” he says quietly. His story highlights the power of recovery and that even after years of despair, a life can be rebuilt.

Such success stories, though still too rare, underline a crucial point: treatment works, and people can and do recover. Debra, a treatment center director in northern Kentucky, shares her own past of opioid addiction to inspire others, proving that those with lived experience often become the most passionate healers in their communities. In Lexington, a restaurant called DV8 Kitchen exclusively hires people in recovery, giving them a supportive job environment; its owners report that rather than chaos, they’ve seen “a flowering of gratitude, loyalty, diligence” among staff, and it’s changed their entire perspective on what people in recovery can achieve. For every life lost that makes headlines, there are many quiet victories – individuals celebrating one month clean, parents reunited with children after getting sober, peer mentors guiding someone else out of the darkness. These personal narratives fuel the fight in Kentucky, reminding everyone why it matters. As one recovered addict turned counselor often tells those just starting out: “All you have to change is everything”. It’s a daunting challenge, but thousands of Kentuckians are meeting it with courage each day.

Fighting Back: Prevention, Recovery and Hope

Confronting a drug crisis of this magnitude requires a multipronged strategy. In Kentucky, a combination of tough law enforcement, expanded treatment access, and innovative harm reduction has emerged – often through trial and error – as the way forward. The approach is comprehensive: choking off supply, rescuing those in immediate danger, and helping people find long-term recovery. “By working together, we are saving lives,” Gov. Beshear said in announcing the latest overdose data. Here’s a look at what that fight entails on the ground.

Cracking Down on Trafficking: Police and prosecutors in Kentucky have ramped up efforts against the drug trade, from street-level dealers to interstate trafficking rings. The Kentucky State Police (KSP) launched high-intensity operations such as “Operation Summer Heat,” a coordinated statewide drug sweep. In summer 2025, Operation Summer Heat 2.0 led to 197 arrests and the seizure of over $640,000 worth of drugs – including kilos of fentanyl, meth and heroin, along with hundreds of illicit pills, firearms, and even stolen cash and property. “This mission was about more than making arrests; it was about disrupting the criminal enterprises that threaten the safety and health of Kentuckians,” said KSP Commissioner Phillip Burnett Jr.. All 16 KSP posts across the state participated, reflecting the ubiquity of the problem. Federal agencies, too, have targeted Kentucky networks, indicting major traffickers importing fentanyl from out of state or overseas. The U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Eastern District runs the HEAT program (Heroin Education Action Team), which not only prosecutes dealers but also sends impacted families to educate communities about the dangers.

On the ground, local sheriffs partner with federal DEA agents especially in high-traffic corridors like Northern Kentucky (a known pipeline for fentanyl coming down the interstates from Detroit and Chicago). In rural counties, limited manpower means officers get creative – using anonymous tip lines, collaborating with neighboring counties, and even enlisting postal inspectors to intercept drug packages. “If we find a source down the road, I call someone in that area to help,” says Sheriff Joe Lucas in Lee County, emphasizing information-sharing across jurisdictions. Kentucky has also stiffened penalties for trafficking fentanyl, while simultaneously urging prosecutors to channel those caught with smaller possession amounts into drug court or treatment diversions instead of prison when possible. The goal: hit the supply chain hard, but treat users as people in need of help rather than purely as criminals.

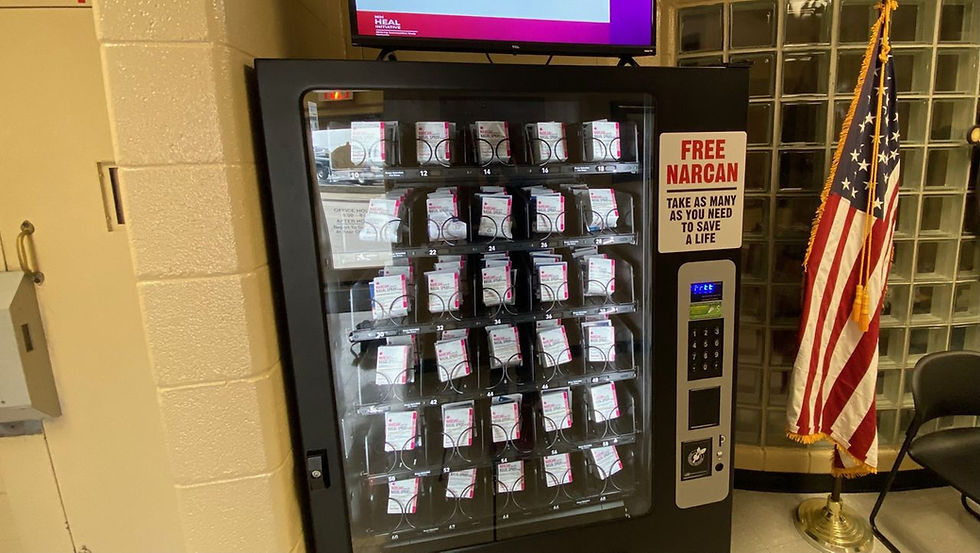

Harm Reduction on the Front Lines: A distinguishing feature of Kentucky’s response has been its embrace of harm reduction measures – pragmatic tools to keep people alive and reduce disease transmission until they’re ready for treatment. Perhaps most impactful is the widespread distribution of naloxone (Narcan), the opioid overdose antidote. Kentucky has made naloxone so accessible that it’s now in health departments, recovery centers, pharmacies, and even vending machines. In Louisville, for instance, the Metro jail’s lobby houses a Narcan vending machine that dispenses free overdose-reversal kits to the public. The state has rapidly scaled up supply: 160,000 doses of Narcan were distributed in Kentucky in 2023 alone, and an additional 170,000 doses in 2024. Van Ingram, Kentucky’s drug policy director, says this saturation of Narcan is “key” to saving lives. “Fentanyl is what’s driving this crisis. If we can ever get a handle on that, I think the success we can have is unbelievable,” Ingram notes, underscoring that naloxone and other measures to blunt fentanyl’s toll are critical.

A Narcan vending machine in Louisville allows people leaving jail to obtain the opioid overdose antidote for free. Kentucky distributed over 160,000 doses of Narcan in 2023 as part of broad harm reduction efforts.

Kentucky has also leaned into needle exchange programs – a policy that was controversial at first in this conservative state, but has proven its worth. As of 2024, there were 84 syringe exchange sites serving nearly 28,000 unique participants statewide. These programs, often run by local health departments, allow people who use IV drugs to swap dirty needles for clean ones, reducing the spread of HIV and hepatitis C and providing a touchpoint for health services. Many exchanges also hand out naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and information on treatment. Indeed, recognizing the reality of fentanyl-laced supplies, Kentucky’s legislature in 2023 legalized fentanyl test strips (previously considered drug paraphernalia). Now, health workers distribute these strips so users can at least check if fentanyl is present in other pills or powders, potentially altering their behavior and preventing a fatal mistake.

Public education and stigma-fighting are another prong of prevention. Across Kentucky, community forums and school assemblies now feature not only experts but also “courageous family members” who share their stories of loss to warn others. The aforementioned HEAT program has presented to thousands of students and parents since 2015, making the epidemic’s costs personal by highlighting faces and names behind the statistics. Meanwhile, mothers like Julie Hofmans deliver heartfelt testimonies to teenagers about the real risk of one bad pill. High schools in both urban and rural areas report that these frank talks – often accompanied by demonstrations of how to administer Narcan – have led to students coming forward seeking help for themselves or a friend. The message is sinking in: this can happen to anyone, and if it does, help is available without judgment.

Expanding Treatment and Recovery: Perhaps the most transformative strides Kentucky has made are in the realm of treatment. Leaders recognized that you cannot arrest your way out of an addiction epidemic – people need treatment for a chance at recovery. Over the past five years, Kentucky has poured significant resources into expanding access to evidence-based treatment, including medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with buprenorphine or methadone for opioid use disorder, residential rehab programs, and community-based recovery support.

By at least one measure, Kentucky is now a national leader in treatment capacity. A 2024 study by East Tennessee State University found that Kentucky ranks #1 in the U.S. in residential drug treatment beds per capita, with about 70 treatment beds per 100,000 people – more than double the rate of any neighboring Appalachian state. “This is great news and more proof that our hard work is paying off,” Gov. Beshear said of the finding. The state has aggressively used federal grants and opioid lawsuit settlement funds to open new facilities and bolster existing ones. A prime example is Addiction Recovery Care (ARC), a Kentucky-based organization that has established a network of treatment centers, including converting a former hospital in Ashland into a 100-bed residential recovery campus. As ARC’s CEO Tim Robinson (himself in recovery) put it, “Our entire team is extremely proud to be part of the strong momentum Kentucky is building as a national model… showing that innovation, collaboration and determination can save lives and transform communities.” ARC and other providers have integrated vocational training into treatment – recognizing that a job and purpose are key to sustained recovery. Programs range from teaching tech skills to, as seen, grooming racehorses.

Crucially, treatment is increasingly accessible regardless of income. Kentucky expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, and as a result over 142,000 Kentuckians received substance use disorder services through Medicaid in 2024. For those who are uninsured, the state launched a Treatment Access Program that will pay for residential treatment for anyone who needs it. Additionally, the Kentucky Opioid Response Effort (KORE), funded by federal grants, has paid for treatment for more than 17,000 Kentuckians and provided recovery support services (like housing, job training, transportation) to another 17,980 individuals in one recent year. Peer support is another growing facet: networks of people in long-term recovery serve as peer mentors and recovery coaches, meeting those just out of rehab or jail and helping them navigate early sobriety. These peers often staff “recovery community centers” – safe spaces in many towns where people can attend support meetings, use a computer to job-hunt, or just have a coffee with others who understand their struggle.

Some initiatives enlist law enforcement in the recovery effort in novel ways. The Kentucky State Police “Angel Initiative” invites anyone struggling with addiction to walk into a State Police post and ask for help; officers will facilitate a treatment placement instead of making an arrest. The program is still small (19 people used it in 2024), but it symbolizes a culture shift – police are being trained to see addiction as a disease to be treated, not a moral failing to punish, especially when individuals voluntarily seek help. In Lexington, the police department even launched a “Substance Use Intervention” office to connect people to treatment rather than charge them, in cases where crimes are minor and clearly driven by addiction.

Meanwhile, community-led recovery programs have flourished. Beyond the innovative Stable Recovery horse farm program that saved John Bowman, there are others: churches sponsor “Celebrate Recovery” groups; nonprofits run “sober living” homes that give people a drug-free residence after rehab; and the state is certifying “Recovery Ready Communities” – counties that meet benchmarks for offering resources like quick treatment access, peer support, transportation, and employment opportunities for people in recovery. Already 21 counties have earned the Recovery Ready designation, covering nearly 1.5 million Kentuckians. One such community resource center is The Hub in Lee County, which opened in response to that county’s high overdose rate. “We meet you where you are, but we don’t leave you there,” is The Hub’s motto. It’s a one-stop shop where individuals struggling with substance use can get linked to treatment, mental health counseling, and basic needs like a hot meal or a shower. “What I would like to see is zero overdoses,” says health director Scott Lockard of his hopes for places like The Hub. “Everyone who suffers from substance use disorder getting the treatment and support they need so they can triumph over this disease”.

Early results from Kentucky’s comprehensive strategy are encouraging. As noted, overdose deaths are down significantly, and Kentucky’s “recovery ecosystem” is now held up as an example. A recent analysis even noted that Kentucky had 14 of the 20 counties with the biggest overdose death declines nationwide. Those counties were largely in Eastern Kentucky – the same region once labeled “ground zero” of the opioid crisis. Experts credit the state’s approach of combining law enforcement pressure on suppliers with wide availability of treatment and harm reduction. “Unlike similar states in the region, Kentucky has become a leader in creating strong Recovery Ecosystems,” the ETSU report concluded. Governor Beshear, at a ribbon-cutting for ARC’s new center, summed up the feeling: “With the help of organizations like ARC, we are working to build a safer, healthier commonwealth for all our people”. But even as he touted progress, he acknowledged the work is not done.

Signs of Progress Amid Ongoing Challenges

Is Kentucky’s battle against the drug epidemic turning a corner? The data and on-the-ground feedback provide cautious optimism. The steep drop in overdose fatalities in 2024 – a 30% decline – is one of the most dramatic improvements seen in any state. It suggests that widespread naloxone, prevention efforts, and expanded treatment access are saving lives that just a few years ago might have been lost. Indeed, the United States as a whole saw a downturn in overdose deaths in 2024 (after decades of increases), but Kentucky outpaced the national trend. Public health officials in Kentucky also report lower rates of HIV and hepatitis linked to injection drug use, attributing that to the syringe exchanges and education. In Lexington (Fayette County), for example, overdose deaths fell from 177 in 2023 to 120 in 2024 – a roughly one-third drop. “We’re seeing a measurable reduction in fatalities,” the city’s health department announced, pointing to collaborative efforts as the cause.

Another positive sign: Drug-related crime indicators are improving. The Kentucky State Police noted in 2025 that overall drug/narcotic offenses recorded statewide fell by 11.5%, alongside double-digit decreases in violent crimes like homicides. While it’s too early to draw definitive conclusions, one theory is that fewer active drug users on the street (because more are in treatment or using harm reduction services) translates to fewer thefts and less volatile behavior. Some communities also report that after implementing quick-response teams (pairs of a police officer and counselor who visit individuals within days of an overdose to offer help), repeat overdoses in those areas declined. In Northern Kentucky, a pilot “law enforcement assisted diversion” (LEAD) program, which directs low-level drug offenders to case managers instead of jail, led to reduced re-arrest rates and better engagement in services.

Perhaps the most heartening progress is anecdotal: the culture around addiction in Kentucky is shifting from one of despair to one of determination. “We’ve been very blessed… I focus on the successes,” says Frank Taylor, the horse farm owner who co-founded Stable Recovery. His program has now graduated over 110 men and expanded to multiple houses, and there’s talk of replicating it elsewhere. Similarly, at the state’s network of Recovery Kentucky centers (a set of 13 rehab facilities targeting homeless or indigent Kentuckians), counselors report long waitlists – not necessarily a positive on its face, but it means more people are seeking help voluntarily. The stigma that once kept folks from admitting a problem is gradually fading as communities rally to support recovery. Churches host recovery groups in their basements; county judge-executives (the top local officials) talk openly about their own family members’ battles with addiction. This normalization of the conversation is progress in itself.

Yet nobody is declaring victory. For every step forward, there are new challenges and lingering disparities. One worrying trend is the demographic shift: after years of the crisis largely affecting white rural communities, overdose deaths among Black Kentuckians have been rising. In 2023, while overall deaths fell, the number of Black Kentuckians lost to overdose actually ticked up slightly (264, from 259 the year before). This suggests interventions might not yet be reaching minority communities effectively, or that fentanyl’s spread is cutting across racial lines in cities like Louisville. Health equity advocates are calling for culturally specific outreach and more services in urban neighborhoods to prevent the opioid crisis from further entrenching racial health disparities.

Moreover, the potency of drugs on the street is higher than ever. Lab tests show that fentanyl in Kentucky is increasingly potent, and sometimes mixed with other novel synthetic opioids (nitazenes) or tranquilizers. These chemical wildcard combinations can defeat even experienced users’ tolerance and pose challenges for first responders (xylazine, for example, doesn’t respond to Narcan and can cause gruesome wounds). Kentucky toxicology reports noted that Jefferson, Fayette, and Pike counties saw some of the highest-potency fentanyl and meth in the state – a dangerous sign that the drug supply is not getting any safer. And while test strips help, they are not foolproof; many users will take the chance even if a strip shows fentanyl present, due to the compulsions of addiction.

Another challenge is sustaining funding and momentum. Kentucky is currently bolstered by a wave of opioid lawsuit settlement funds – nearly $1 billion allocated to the state over coming years. Half of that money goes to a state Opioid Abatement Trust, half directly to counties and cities. Already, a state commission has awarded $85 million in grants to about 130 organizations for treatment, prevention, and recovery programs. This influx is turbo-charging the response now, but it’s largely one-time money spread over about 18 years. When the settlement dollars taper off, Kentucky will need to ensure its programs – whether it’s paying for treatment beds or hiring school counselors – remain funded through general funds or other sources. “Counties take the stewardship of opioid settlement funds seriously and are making data-driven decisions to address the unique needs of their community,” says Lauren Carr of the Kentucky Association of Counties. The hope is to invest in programs that become self-sustaining or that demonstrably reduce future costs (for example, spending on treatment now may save on incarceration or foster care later). Transparent tracking is in place: as of July 2025, counties must publicly report how they spend their settlement shares, to ensure accountability and sharing of best practices across the state.

The Road Ahead: What More Can Be Done

Ask ten stakeholders in Kentucky how to solve the drug crisis, and you might get ten different answers – but often, the solutions are interlocking. Experts and community members alike agree that a multifaceted, sustained approach is needed to truly turn the tide. As Kentucky looks to the future, here are some of the key strategies and insights on what more could be done:

Target Fentanyl at its Source: Fentanyl is now the driving force of the epidemic, so stopping its flow is paramount. This means continued pressure on international and interstate trafficking. Kentucky’s Attorney General and congressional delegation have advocated for stronger federal action to disrupt supply chains from China and Mexico (where precursor chemicals and finished fentanyl often originate). At the state level, this could involve tougher penalties for importation and equipping law enforcement with better technology – like portable spectrometers to instantly identify fentanyl in the field. Some have suggested laws to regulate pill presses and precursor chemicals to make it harder for local dealers to manufacture counterfeit pills. As Van Ingram said, “If we can ever get a handle on [fentanyl], the success we can have is unbelievable”. That “handle” may involve everything from international diplomacy to local mail parcel screening.

Expand Treatment – and Innovate: While Kentucky leads in treatment capacity now, gaps remain, especially in rural areas for specific services like detox and psychiatric care for co-occurring disorders. Telemedicine for addiction treatment, which grew during the pandemic, should be expanded to connect patients in remote Appalachian hollers to Suboxone-prescribing doctors or therapists. Also, new models like mobile treatment clinics (RV-style units that travel to underserved communities) could be deployed with the settlement funds. Importantly, treatment needs to meet people where they are – literally and figuratively. That might mean more low-threshold services like medication-first treatment (providing MAT without requiring full abstinence or program enrollment right away) to attract those who are hesitant. And special populations need attention: pregnant women with addiction (to prevent NAS births), incarcerated individuals (with better jail treatment programs and reentry support), and youth. Adolescent addiction treatment services are notably scarce in Kentucky; creating youth-specific outpatient programs or recovery high schools could fill a void and prevent young lives from derailing.

Sustain Recovery Supports: Getting someone off drugs is one thing; keeping them off is another. Many in Kentucky emphasize the need to build out the long-term recovery infrastructure. That includes more transitional housing (sober living homes) so that people aren’t returning from rehab to the exact environment that triggered them. It includes job opportunities for those in recovery – perhaps by expanding initiatives like DV8 Kitchen or encouraging employers with incentives to hire people in recovery. Frank Taylor’s vision with Stable Recovery points to a larger idea: “You’ve got all this addiction, and you also have a problem with no workers… these two major problems can actually help solve each other”. By training people in recovery to fill labor shortages (in trades, manufacturing, etc.), Kentucky can tackle addiction and unemployment together. The state could use some settlement or workforce funds to subsidize apprenticeships for those in early recovery, giving them a foothold in the job market. Rebuilding family relationships is another pillar – more family therapy programs and support groups for families could strengthen the home environments that recovering individuals return to.

Address Root Causes – “Nothing to do” and Beyond: Perhaps the hardest but most profound work is to heal the underlying wounds that fuel addiction. In Eastern Kentucky, residents have long said that lack of opportunity and activities for youth leaves a void that drugs fill. Investment in community development is key: creating jobs in these regions (through economic development initiatives, perhaps clean energy or tech jobs to replace mining), and investing in social infrastructure. Reopen the public park. Support a youth center or a sports league. These are not “drug policies” in the traditional sense, but they are prevention in the broadest sense. When Travis in Clay County said “there ain’t nothing around here to do… that’s why everybody turns to drugs”, it was a call to action to give communities hope and young people alternatives. The state and federal government can channel grants to build up rural communities – something already happening in small ways (for example, through the ARC (Appalachian Regional Commission) and other programs). Additionally, tackling poverty and improving education are long-term solutions to reduce vulnerability to addiction. Better access to mental health care, starting in schools, could catch issues early before they manifest as substance abuse.

Continue to Fight Stigma and Build Empathy: Many experts stress that solving this crisis isn’t just about money or programs, but also about changing hearts and minds. Stigma around addiction can prevent people from seeking help and can sap political will for funding programs. Kentucky has made great strides in recognizing addiction as a disease; that needs to continue. Public awareness campaigns highlighting recovery stories (to show that recovery is possible) and the science of addiction can further erode stigma. Training more first responders and healthcare providers in trauma-informed care – understanding that many who become addicted have underlying trauma – will improve the compassion and effectiveness of services. And the community dialogues, like those with the HEAT families or town hall meetings, should carry on. The more people talk openly, the more the wall of shame comes down. This also extends to how we treat those who do relapse or struggle repeatedly; as long as they are alive, there is hope for another chance, so the priority is keeping them alive and engaged.

Innovate with Data and Technology: Kentucky’s use of data has been a strength (through KIPRC’s surveillance system and dashboards), but it can go further. Predictive analytics might identify hotspots or emerging drug trends faster. For example, analyzing ER visit data for overdose spikes could trigger rapid response outreach in a given county. Expanding wastewater testing for drug metabolites can act as an early warning system for where xylazine or other new adulterants are spreading. Technology can also help connect people to resources: the state’s online portal “FindHelpNowKY” allows anyone to search in real-time for available treatment slots. Continued investment in such tools, and ensuring people know about them (perhaps a public info campaign on how to find treatment), could lower barriers.

As Kentucky pursues these strategies, there is a palpable sense that the state stands at a pivotal moment. The past few years have shown that progress is possible – overdose deaths can be brought down, lives can be saved. But it will require staying the course and not letting up. “We won’t stop until every Kentuckian is saved from addiction,” Governor Beshear pledged. It’s an ambitious goal, but that kind of commitment from leadership, combined with grassroots community grit, is what it takes.

In a humble courthouse in rural Kentucky, a judge listened recently to a man in recovery describe how he turned his life around. The judge, moved, chose hope over punishment, allowing the man to continue his treatment rather than serve a prison term. In that moment, one saw the embodiment of Kentucky’s evolving approach: tough when needed, but compassionate at its core, rooted in the belief that every life is worth saving. The road ahead is long, and new challenges will surely arise, but across the Bluegrass State – from the hollers of Appalachia to the suburbs of Lexington – there is a resolve that did not exist a decade ago. A resolve to come together, to heal the wounds, and to ensure that fewer families have to endure the pain that so many already have. Kentucky’s drug crisis was built over years, and it will take years to undo. But as personal stories of recovery emerge, overdose numbers fall, and communities invest in solutions, there is genuine hope that the tide is finally turning in the Commonwealth’s favor.

Sources:

Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy – 2024 Overdose Fatality Report Highlights

Kentucky Governor’s Office – Press Release on Overdose Deaths Decline (May 2025)

Kentucky Association of Counties – Opioid Settlement Fund Reporting (June 2025)

Kentucky Lantern – “For second year in a row, Kentucky overdose deaths decrease”

Spectrum News – “Kentucky mother on a mission to raise awareness about fentanyl”

LEX 18 News – “Lee County faces high overdose death rates despite statewide decrease”

Poverty Solutions (Univ. of Michigan) – “Disinvestment in rural Kentucky leaves ‘nothing to do’ but drugs”

Washington Post – “At a Kentucky farm, star racehorses help people fight a monster: Addiction”

East Tennessee State Univ. – Study on Kentucky’s Treatment Capacity & Outcomes

University of Kentucky experts – Insights on evolving drug trends in KY

U.S. DOJ, Eastern District KY – Heroin Education Action Team (HEAT) mission

Kentucky State Police – Operation Summer Heat 2.0 Results (July 2025)

Kentucky Injury Prevention & Research Center – OUD prevalence study (2023)

Additional reporting by Kentucky Health News and Interviews with local officials and families (2023-2025).

😀